Documenting the Individual: My Response to Enforced Allegiance Under a Violent Regime

- Sepanta Saeb

- May 6, 2025

- 4 min read

By Sepanta Saeb

Sepanta's Website

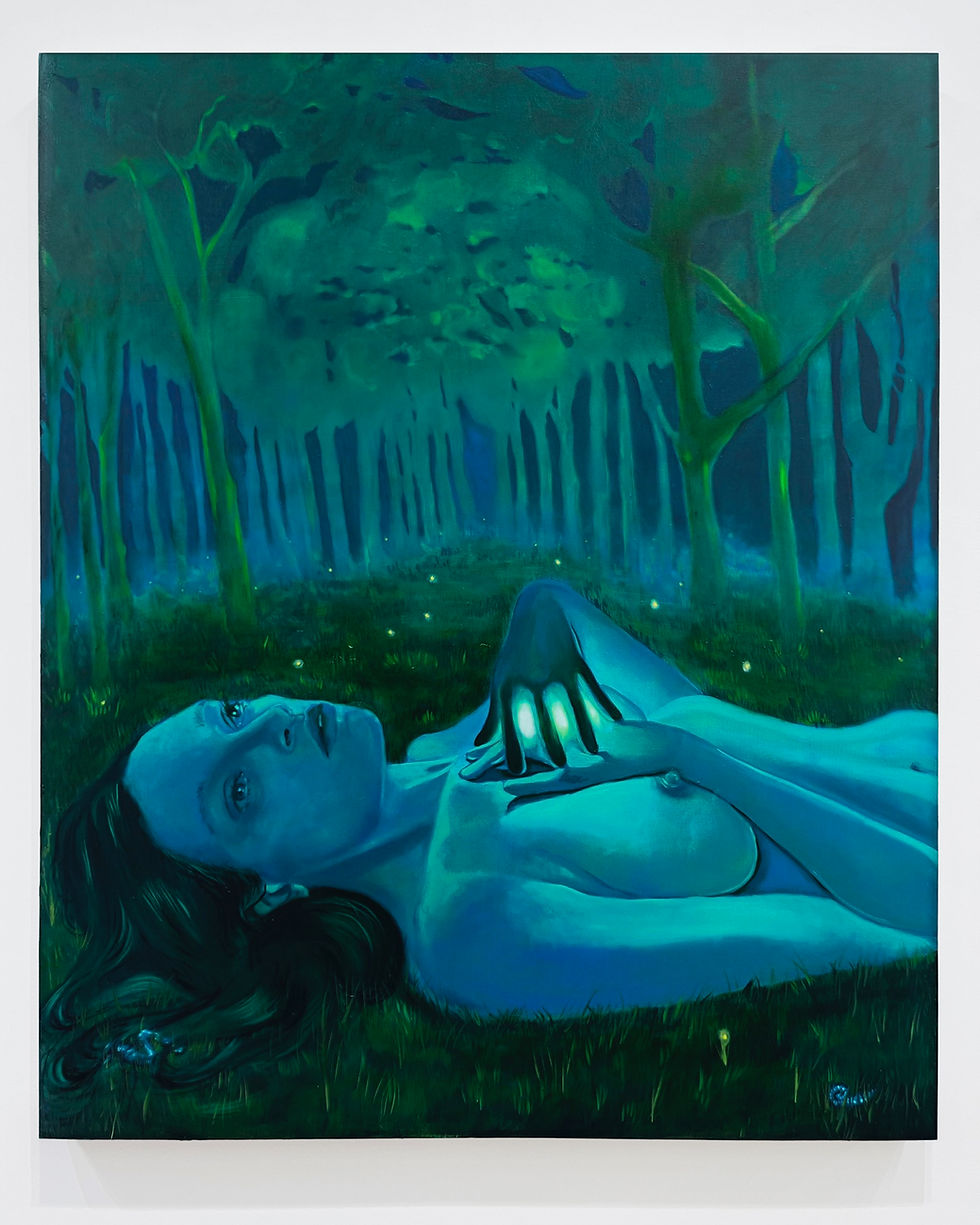

Growing up far from Iran but still within its cultural space, I often felt like I was speaking a language that had no safe place. My queerness and my heritage were never in conflict, but others constantly framed them that way. In my work, I chose to paint faces and censor mouths not only to reflect state violence but also to echo how queerness is erased in diaspora narratives. The repetition in my portraits mimics how identities become flattened, whether by the regimes or Western media, where complexity is irrelevant, where we are asked to perform palatably, even in our pain.

One of those portraits is titled, God Loves You, But Not Enough to Save You. These words do not comfort; they haunt. They echo through the streets of Tehran, through the eyes of women forced into silence, through the breath of queer Iranians hiding in plain sight. In these words lives a brutal truth: in a country where the divine is state property, love is not unconditional—it is regulated. Measured. Denied.

This phrase is the heart of my work. It is a bitter prayer, a question left unanswered. It speaks to the people of Iran—those who cry out for change, for dignity, for democracy—and is met with bullets, prison, and exile. It speaks to the ones who march, who mourn, who scream names into the sky, asking why God’s supposed love does not protect them. It’s a phrase carved from grief, from the sharp edge of betrayal by those who claim to speak on behalf of the divine.

Religious leaders in Iran do not simply guide faith; they stand between the people and freedom. They decide who is pure enough to live without fear. Their words become law, their sermons policy. They promise salvation, but only after obedience. They offer God but not justice. They weaponize religion to control, suppress, and erase. It is not God who denies us, but those who place themselves in His image.

Under this regime, democracy becomes a myth, a set of empty rituals. Votes are cast in shadows, not counted. Voices rise, but they are not heard. Instead, the state relies on surveillance and data—tracking movement, collecting faces, and building profiles not for representation but for punishment. Data, which may serve transparency and equity in other places, becomes a tool of fear. It catalogues the undesired. It criminalizes the personal. It erases the inconvenient.

As a queer Iranian, I have always known what it means to exist between barriers—of faith, of body, of belonging. I carry stories from a country that tries to forget us, erase us, and punish us into silence. But there is resistance to remembering. There is power in witnessing. And so, I make work not to ask for saving but to speak the unspeakable. To name what has been denied.

This is why I layer Persian calligraphy onto the bodies—not as ornament, but as reclamation. These words belong to us, not to the regime holding power over us. In placing them over erased faces, I claimed something in what had been deliberately hidden.

Art became the one place I could speak without apology. It allowed me to sit with denial, rage and faith tangled together. In a world that constantly demanded I simplify myself—artist or activist, Iranian or queer, grieving or enraged—art allowed me to be all of it at once. My work is not easy to do, but it is honest. It is mine.

This is not about sorrow—it is about refusal. It is about the people who continue to rise despite being told they are alone. It is about women who burn their veils and men who mourn their lost sisters. It is about queer Iranians who dare to love in a place where love itself is criminalized. It concerns those who speak God’s name and still choose justice over obedience.

Our existence is not static—it is defiant. In the face of censorship and exile, we create. We archive what others erase, speak what others silence, remember those deemed unworthy of saving, and share their stories.

If God loves you but not enough to save you, we must become each other’s salvation through art, voice, and memory. My work is a testament to the fact that we existed, resisted, and spoke. We did not wait for heaven.

Sepanta Saeb is a Toronto-based visual artist and photographer whose practice delves into identity, memory, and belonging. A queer, first-generation Persian immigrant, their work reflects layered narratives shaped by displacement, heritage, and queerness.

Through a richly symbolic visual language, Sepanta interrogates the cultural tensions between queerness and Persian tradition, reimagining inherited motifs as vessels for resistance, affirmation, and coexistence. Their art becomes a site where contradictions are not resolved, but instead embraced as part of a multifaceted self: “I exist as both a Persian and a queer person simultaneously, and many more.”

With a deep commitment to visual storytelling, their work bridges classical traditions and contemporary queer perspectives—producing evocative, culturally rooted, and emotionally resonant pieces.