Myths, Fallacies, and Realities about Working as an Artist: An Interview with Nicole Collins

- Laura Thipphawong

- Feb 22, 2025

- 15 min read

Updated: Jun 1, 2025

By Laura Thipphawong

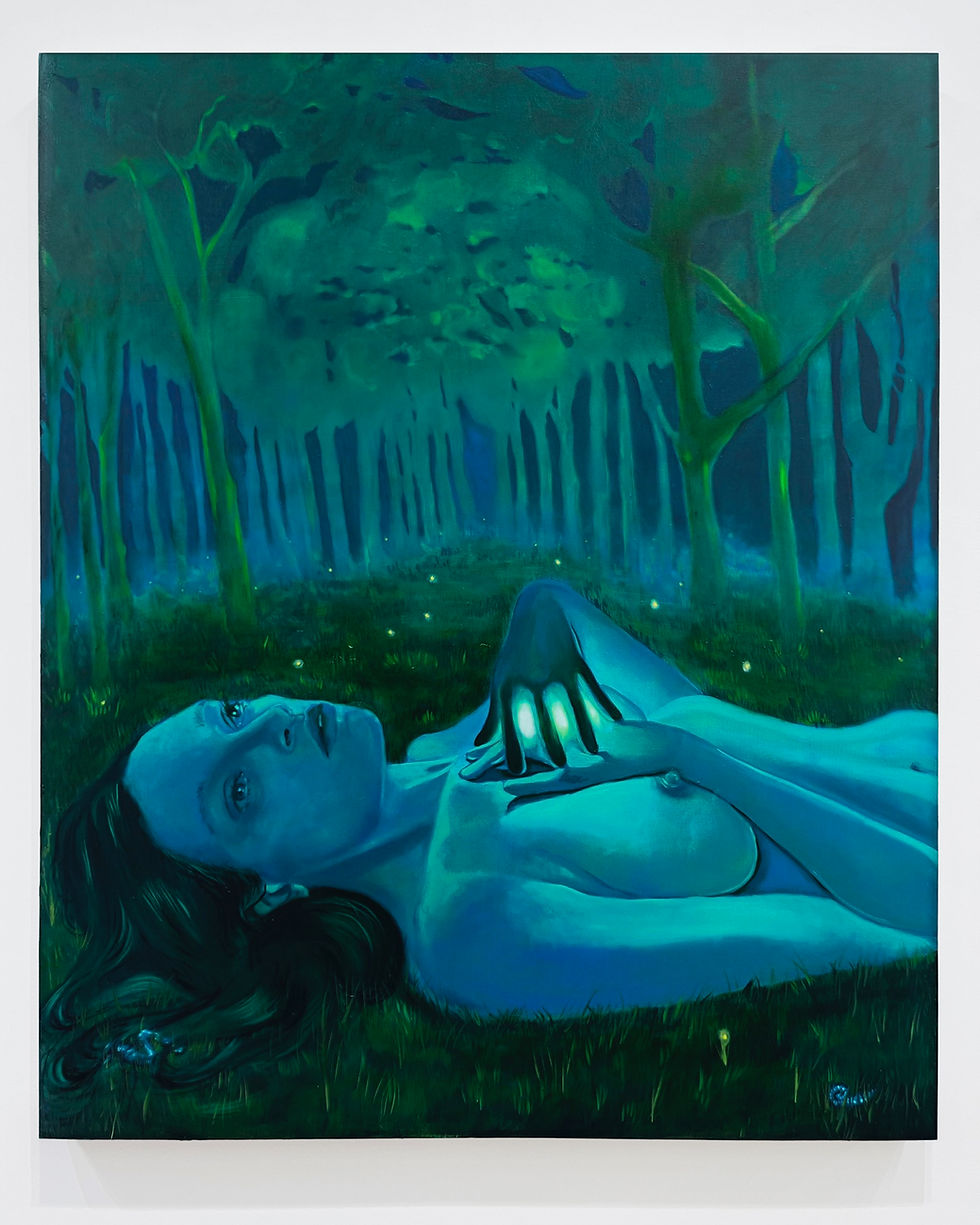

Nicole Collins, Website: www.nicolecollins.com, Instagram: @nicolecollinsartist

This interview is part of The Professional series – articles on the topic of life as a working artist.

The reality of life as a professional artist is something I've wanted to write about for years. It's a topic not well-represented in the public, the media, the schools—and as artists, we are often complicit in perpetuating a host of false narratives about life in the arts. These narratives tend to either romanticize poverty, indirectly represent a lifestyle afforded by generational wealth, and effectively stigmatize the necessity for most artist to work supplementary jobs alongside their art careers. When I decided I wanted to contribute a pragmatic spin to the discourse—something less ephemeral than a closed-door conversation—I immediately knew I wanted to interview Nicole Collins.

Nicole is a successful artist. She's been exhibiting in commercial galleries and museums worldwide for over thirty years. Her work has been featured in modern art history textbooks. Her 20-page CV boasts dozens of group shows, art fairs, residencies, and a continuous steady stream of solo exhibits in multiple established and highly sought-after galleries, including the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO). Her art practice is expansive. She also has a full-time job.

I met Nicole in 2012 at OCAD University, where she works as an associate professor in the Drawing and Painting program; hers was the first class I attended as an official university student (I had audited several UofT courses previously), and I was nervous, to say the least. But not the typical out-on-your-own kind of nerves that usually plague the first-year student. I had decided at the age of 29 that it was finally time to follow my dreams and enroll in university. After fourteen years in the workforce and six years of blindly making my way through the Toronto art scene as a self-taught outsider, I was going to immerse myself in the art world.

To be clear, I never had any illusions of one day supporting myself through my art practice alone—I still don't. By that point, I had enough experience as a working artist to understand the fickle nature of the art market, one too unstable to confidently rely on for income—at least, not when you're on your own, and me with no partner, no roommates, no parental support, no savings. What was shocking, though, was how many of the students seemed never to have had an open and honest discussion with any working artist about what that lifestyle was really like. The assumption for many was that in coming to OCAD they would discover the key to success. Yes, they would work hard and study, but more importantly, they would figure out the secret recipe for “making it” as a full-time artist.

Now, it should be said that for the purposes of this article and interview, we're defining a full-time artist not by the hours you put into your art practice, but by the designation of working ONLY as an artist. Because this is the dream, right? This is the goal for all the hopeful, non-cynical, bet-on-yourself-type burgeoning artists out there. And it's no wonder. Scour the internet and you’ll find countless BuzzFeed-esque listicles touting five ways to make a living as an artist, or ten artists just like you who have found a way to "make it.” Artists themselves will mislead you about how working hard and networking was the way they got to that coveted full-time artist position. Great, so go to it, everyone. If this is the case, we'll all be full-time artists soon.

But that's not the case, it’s just the polished-up version of the artist that popular media neatly presents: a social-media-style reductionist portrayal of a life that we’ve been aspiring to since even before the time of social media. It's the portrayal of a person living outside the confines of normal society, a sometimes pretentious and maybe out-of-touch eccentric who spends all their time either in their studio or gallivanting around town. They're so good at what they do that it's all they do. It's an image that many artists feel the need to uphold, and it's a myth that needs debunking.

On that first day of school, Nicole said something that has since stuck with me. While we all took turns introducing ourselves for the requisite get-to-know-you exercise, one student introduced themselves along with the assertion that they intended to be a full-time artist after graduation. Nicole paused and looked inward—after a moment of contemplation, she informed us of the ethical quandary in supporting that kind of thinking. Not that she wanted to crush anyone's dreams or discourage would-be artists from pursuing their creative passions, quite the opposite; she wanted to prepare students for a long-term career in the arts by stating the cold, hard facts up front, that working as a full-time artist without supplementary financing is an improbability.

Nicole was gracious enough to sit down with me upon my request to discuss this still-relevant topic, a topic that's maybe more relevant now than ever. Here's what she had to say.

Laura Thipphawong: Let's just get right into it. What are the post-secondary arts institute's ethical responsibilities for providing real-world guidance to students hoping to make a career based solely off their art, and do you think these institutes are doing enough to fulfill these obligations?

Nicole Collins: Okay, heavy-hitting right out of the gate! So, it's worth stating that I have been teaching at OCAD University since 2003, and before that, I went to University of Guelph from '84 to '88 and then got my Master’s of Visual Studies at the University of Toronto in 2009. I also taught at the Toronto School of Art. And I'm mentioning these things to contextualize my answer, because I'm also a practicing artist, and when I was a student, there was zero professional practice education – nothing at all.

The artists who taught us at the university would anecdotally tell us about their practice, or we'd go visit their studio. One artist offered to give us a crash course in how to write a grant and how to write a CV, because we hadn't even learned how to write a CV. So, when I came to Toronto with my partner, who's also an artist, and a lot of our friends, we all immediately participated in workshops that were offered by organizations like Visual Arts, Ontario, which doesn't exist anymore, but was a huge, important gateway to professional-practice knowledge. And then it was just like, figure it out. Now, here we are all these years later, and your question is, is there an ethical responsibility?

And my answer is absolutely, yes. If I'm participating in a degree-conferring institution essentially preparing artists to go out to the world, we have that ethical responsibility. How are we doing? You know, I can only speak to the place where I work, where there are quite a few good tools available for artists, for students preparing to go out into the world. There's CEAD, the Center for Emerging Artists and Designers, funded by RBC. It's a group of administrators, organizers, and educators who focus on presenting workshops to students in preparation for entering the market. They have workshops on best practices for writing grants. They offer competitions for studios. It's a really good thing.

Students do need to self-start and go there and do those things that aren't in the curriculum, but it's available. It's also available to students after graduation, which I think is the most important thing. Because while you're a student, you're studenting. There's so much going on, students are even more strapped for time now than ever. They're commuting from farther away, because it's next to impossible to live in the city. They are either working one or two part-time jobs, or a full-time job. People are completely oversubscribed.

Every single day, I meet with a student who's trying to figure it out: how do I do all the things I'm supposed to do? And I often have to say to them, you can't, something's got to give. I can only provide a certain amount of guidance, but this is for each of us to figure out on our own. Pressures now are unprecedented, and it's really troubling. I don't know any other way to say that. It's troubling for the students and the people working in the institutions. In Ontario, we are being tasked to provide the same education with far less money. So, tuition freezes, that's good, but funding is also completely gutted, provincially and federally.

So we have to be creative, be agile, respond to the pandemic, create new ways of learning. But if you want to have a studio-based education where you can actually be in community with your peers, making things together in conversation, you cannot do that with 150 students. It's not possible. In the past, we had 4th-year courses that allowed for us to deliver the kind of curriculum I think is necessary, like having workshops on how to write grants and how to think about grants, and we would talk about the commercial gallery system, what it is and how it works. In order to teach these things, we need time together. We need reflection back from people. I'm speaking to the problem with 150 people: it's fine if you just want one person blasting out information, but how do you have meaningful engagement and conversation, which is where the meat of this kind of education lies.

And when I say conversation, I also mean conversations with guests, because we know there are people figuring out how to make their art and use all the various tools that exist today that didn't exist for a long time. They make sales, and then pivot and make prints, and make posters and stickers, and then do presentation, you know, like the kind of really agile work skills that are needed today. All the courses that used to include those things have effectively been destroyed. I feel that it's really important to know that this is happening. They are being destroyed by the stresses of finance that are being bent upon the university. And so, your question really is fraught because: do I have an ethical responsibility? Absolutely! Am I being given the ability to actually do what I feel should be done ethically? No.

It would be really easy to just blame administration, but it's not just them. They're being forced to make decisions, and it really sucks. But I do still try to help students prepare for the real world, even when it's not in the curriculum. I push my final critiques of the artwork up a little bit in the course so that the last class is an open space, and that's where we often talk about these things, especially in 3rd and 4th year classes.

Laura Thipphawong: The next question probably has an obvious answer based on what you just said, but is the art world a meritocracy? How far is anyone guaranteed to get in the arts if they are both truly talented and hard-working?

The art world. The art world has been a lot of different things through history. Can I use one art world as an example, let's say, early Renaissance era, Florence. Because of Vasari, who wrote about all the superstar artists, and the idea of the master. Well, you know, it's a white patriarchal culture, but it's not only that—Florence is the birthplace of banking, so it's also money.

We think of meritocracy as in skill, because there's no doubt that those artists were incredibly talented. And, by the way, I believe that talent and being hardworking are two intersecting things, because I really believe that somebody who might not be considered talented as a child, for example, can actually become one of these masters. But I'm very suspicious of the word talent, especially in today's context. I think that it was a meritocracy in the sense that they were super-skilled, but they were also funded. No doubt there were some really talented kids, young white boys who could draw really well, but were not identified or didn't get into the right spot at the right moment, and who just disappeared. I think that's true globally all the time, that people who have incredible skills and talents do not thrive because they may be missing a rich parent, or they may be missing mental health care.

It could be that all these things have to coalesce for somebody to actually get from talented and hardworking to big success. We know that across millennia, there have been armies of women, people of colour, and men, white men, who have never fully realized their potential, because a bunch of different elements have to come together in order for them, as individuals, to rise and thrive.

So, the term meritocracy is just a great big pile of bullshit for me. I think the word has no meaning. Right now, we're in this difficult political moment, and the word meritocracy is being tossed around. I do believe in being hardworking. I know from experience that somebody who has even moderate skills, if they bring the elbow grease and the energy and the commitment, they can really shift to another place through hard work. So, I'm more interested in that. But hard work requires support.

You can be as hardworking as can be. But if you have to work three part-time jobs while you're a student studying art, you are not going to be able to improve your work in the same way that the person who has your equal amount of so-called talent, but who doesn't have to work. When someone doesn't have to work and can spend all their time practicing, they're going to get better.

This is a fact. I've seen it over and over again, and you know, honestly, I'm taking nothing away from the people who actually managed to rise. Good for them, you know, when I've encountered students who have that kind of great opportunity, they have financial stability, and they have some skill, and they have passion, I always say, don't waste it. If you have parents who are willing to fund your art practice for the first few years while you get out of school, I'm not going to waste any time being jealous or resentful of somebody like that. I'm going to say, don't you waste it.

Laura Thipphawong: Because they’re lucky.

Nicole Collins: And they should know and understand how lucky they are! I appreciate the people who recognize their privilege and understand it. And there's a lot of different kinds of privilege that take different forms.

But there's no guarantee. And you know it makes me really sad, because I have seen creative people who are just shining lights, and they couldn't survive it, and it's really heartbreaking.

There's another piece I'd like to throw in there. It's really important. You can be hardworking, but you've got to take care of yourself.

Laura Thipphawong: Sometimes the idea of hardworking is to just grind, grind, grind, right?

Nicole Collins: You grind yourself down into the ground, and you deplete, and if you don't take time to replenish, then you burn out. That's true of all aspects of life, but especially in the creative arts, because we equate being hardworking with constantly making. And we forget that part of being hardworking is actually slowing down, taking time to reflect, to have relationships with family and friends, and to understand that's where some of the replenishment can come from. There's also this idea of a timeline. Forget it! So many young artists are like, "Well, I'm old. I'm already this age, and I haven't done this yet." So you'll do it later, or not at all, or you'll figure out some other way.

Yeah. So, no meritocracy.

Laura Thipphawong: No guarantee.

Nicole Collins: No guarantee, but… you'll have an interesting life.

Laura Thipphawong: You'll have the life that you willingly pursued.

Nicole Collins: It just might not look like what you thought it would look like. I didn't go to art school until I was 23 or 24, when everybody else was 17 and 18. I felt like an old lady, and I had no financial support. But you know, ultimately, what it comes down to is a comparison. Comparison to others is toxic, right? It does not help you. Of course you're going to do it, compare yourself, but you should try not to.

Laura Thipphawong: That segued nicely because my next question was about financial support. It's another thing that people don't talk about openly, that there's a huge leg up for students and artists who have financial support. It's as if people don't want to admit that this disparity exists. Maybe those who have been supported are afraid they won't get credit for their hard work or talent if people are made aware of their financial advantages. Maybe those who don't have those advantages worry that they won't be taken as seriously as an artist because they also work another job, maybe a job that has nothing to do with art.

But it's just the reality that most professional artists are working day jobs to financially support themselves, and most full-time artists, who work only as artists, are financially supported to some extent – by a spouse, a parent, a trust fund. Are we still just trying to uphold a perception of the artist as someone who has risen above based solely on being good enough, and is this harmful to artists? I know everyone wants to be the unicorn, but the full-time, self-made, self-sustained artist is extremely rare, and doesn't even look the way you think most of the time.

Nicole Collins: It's harmful to everybody. With teaching, for example, everybody knows you're teaching, and what I found back when I was a young artist, was that artists who didn't work (which was more of a possibility back then), their persona was, "I'm a full-time artist," because being a full-time artist was the only serious kind of artist. And of course, working does get in the way of your practice. I love my job, it's a great job, and now I'm a tenured professor, but I cannot have the same practice as somebody who works part-time or not at all. There's no way. The expectations on my time are very high, but the trade-off is, I have a more comfortable life. I can afford to buy art materials.

But if you pick an artist who's doing well, based on your perception—you're reading articles about them, or whatever—a lot of them actually still have jobs, but they don't talk about it. I'm not knocking these artists, because it has been historically difficult to be taken seriously if you make it clear that you work another job.

There is a lot of secrecy about money when it comes to the art world, and any time I meet somebody who's open about it, I really value that. The less we hide, the more chance there is to have truly connective engagement.

And it's also worth noting that the unicorn is only the unicorn because of a whole bunch of people who are contributing. Maybe it's a patron. Maybe it's a life partner who's a doctor or a lawyer or who makes enough money that the artist doesn’t have to work. Maybe it's family money, inheritance. Maybe it's that their work has enough freight to be sold in multiple markets. But there's still a kind of window. You make your sales, and then people have your work, and maybe, if a patron is really rich and they want to really support you, they buy more than one or several, and so they collect you. Possibly. But for an artist to actually make a living off sales of their work alone, they have to be represented in multiple area markets. So that means you've got to get out of town and forge relationships in other places, which is extremely difficult. That's great when it happens, but it's a monumental task. And, by the way, you have to keep making amazing, excellent art at the same time as networking and doing all these other things.

[We're held back by] this Renaissance-era illusion of a genius all alone in a studio making things, and then somebody coming along and taking it and showing it to the world. But those geniuses, they ran ateliers filled with people, including people working in slave labor, who did all the foundational work so that the genius could put the finishing touches on it. Artists of that caliber were actually working as managers. And there are contemporary artists doing this too, who are at a high echelon, and they have to produce on a magnified scale to satisfy a global market. They're not sitting alone making these paintings, they're working within a system with a lot of people helping to produce the work.

Laura Thipphawong: So, in light of these realities, how can we navigate the demands of being a professional artist today – working supplementary jobs, advocating for ourselves, networking, finding time to be inspired? How can artists balance their need to create and the need to support themselves?

Nicole Collins: One word: community. We are living in a moment where every social pressure is driving us apart and isolating us. I can't tell you how close I am to getting rid of my smartphone. There are these articles in the New York Times about people who have done it and are on flip phones instead, and they're walking around their neighbourhood putting up posters on poles. I’ve seen it, artists are forming their own communities by putting up posters saying, let's get together and draw, or something like that. I think this is the future, and I love it. Community is under attack by our governments and by corporations. Capitalism wants you alone in a room with a screen, buying shit and not talking to people in meaningful ways.

I've seen students meet in art school, and sometimes they pool what money they have, and they rent a space to make and show work. They're talking to each other. They're sharing information about opportunities. They're cooking food together. They're going for walks. They're crying, and you know, taking care of each other.

They're doing it themselves, not waiting around for other people to do it. You know you can't wait to be found. There are too few opportunities and not enough people out there with the vision to see the beauty of what you're doing. So, you've got to put it out there. And I know that's another job, but if you're doing it with a bunch of friends, you know, it's much more doable.

We recently invited the artist and paint-maker Anong Beam from Beam Paints to come for a public talk, which was co-presented with the Global Centre for Climate Action to launch the OCADU Sustainable Colour Lab. I visited her paint-making facility on Manitoulin Island, which is also her home, and I was blown away by the community there. She's an artist, and she's also creating a business with other creative people that's so positive and so generative. You could tell that the creativity of the artist was baked into the whole thing, and it has ethically driven how those things are made.

It just reminded me: artists working together is always better. I really feel like that's been kind of diminished in the recent decades. It's up to us to restart it.