Frances Matassa - Artist Profile

- Jan 7

- 7 min read

Website - www.francesmatassa.com

Instagram - @francesmatassa

Why do you make art?

I make art because it’s a way for me to connect and process. My grandpa was an artist, mainly a painter, and he taught me and my sister how to draw as children. I never thought I was good enough to do it as more than a pastime because I wasn’t able to draw hyper-realistically. After I was sexually assaulted as a teenager, I withdrew from myself and struggled to articulate all that I was holding. I ended up dropping out of college after the first year and would go to work and come home and draw because it was something I could focus on (blend, erase, hatch, repeat) to keep my mind occupied. Drawing became a refuge. At first it was a distraction, but eventually I used it as a way to face what I wasn’t able to put into words. I learned to do that when I decided to go back to school to pursue art. One of the first paintings I made in school was about the fractured relationship between my mind and body, and sharing it with the class, I felt a release that I still chase when I’m making art. Since then, I ended up dropping out of that school and moving to New York. It wasn’t until COVID and lockdown that I decided to go back and finish my BFA. But in all that time painting had become not only how I processed things that have happened to me but I also learned how to a symbolic language to talk about it. Through my figures, color choices, and recurring motifs, I can express those experiences without being strictly literal, creating space for transformation.

How do you feel when you’re making art?

When I’m in the right headspace, I get into a sense of ease and flow. Part of my mind is always with the canvas, very calculated and present; thinking through technique, art history, references, color theory, the ways light can bounce off the form. But there’s another part of my mind that is entirely somewhere else. Memory can be a tricky thing when you have trauma, and I know that is true of me. I have a pretty foggy memory, but painting often unlocks little sensory recollections. It’s often smells and sounds that bring me back somewhere. The sound of trickling water while I watch dragonflies zoom through the air in the park, the smell of wet grass, or morning dew beading and sliding down the nylon of our tent while camping at the crack of dawn. I try to hold onto those fleeting moments and hope that they seep into the work. My process tends to be very embodied, balancing that structure with impulse and instinct. Even when I am having a bad day where I’m struggling with the canvas, the act of painting itself often grounds me. Even if I have to go back and start from scratch the next time I go into the studio, because it didn’t turn out well. My hope is that this layered experience of technique, memory, and presence translates into the painting, making them feel sensory in a way. Even though they are often in a moment of stillness, I don’t want them to feel static.

What are the major themes of your work as an artist and why do you work with these themes?

The central theme of my work right now, and for the last few years, is how the body holds trauma. That focus branches into subthemes that I explore like dissociation, derealization, compartmentalization, memory that slips or fragments, and the struggle to feel at home within one’s body after a period of dissociation. I’ve done a couple series on this idea. A few years ago I was mainly painting figures that were contained within some kind of box within the frame of the canvas. The walls of the “box” would often be reflective of a landscape or the outside world, but the figure would always be alone within those walls. That series was really focusing on the feelings of isolation and disconnectedness that brew during dissociation. I mainly did those paintings during COVID, so I think that definitely contributed to some of the imagery and feelings of isolation.

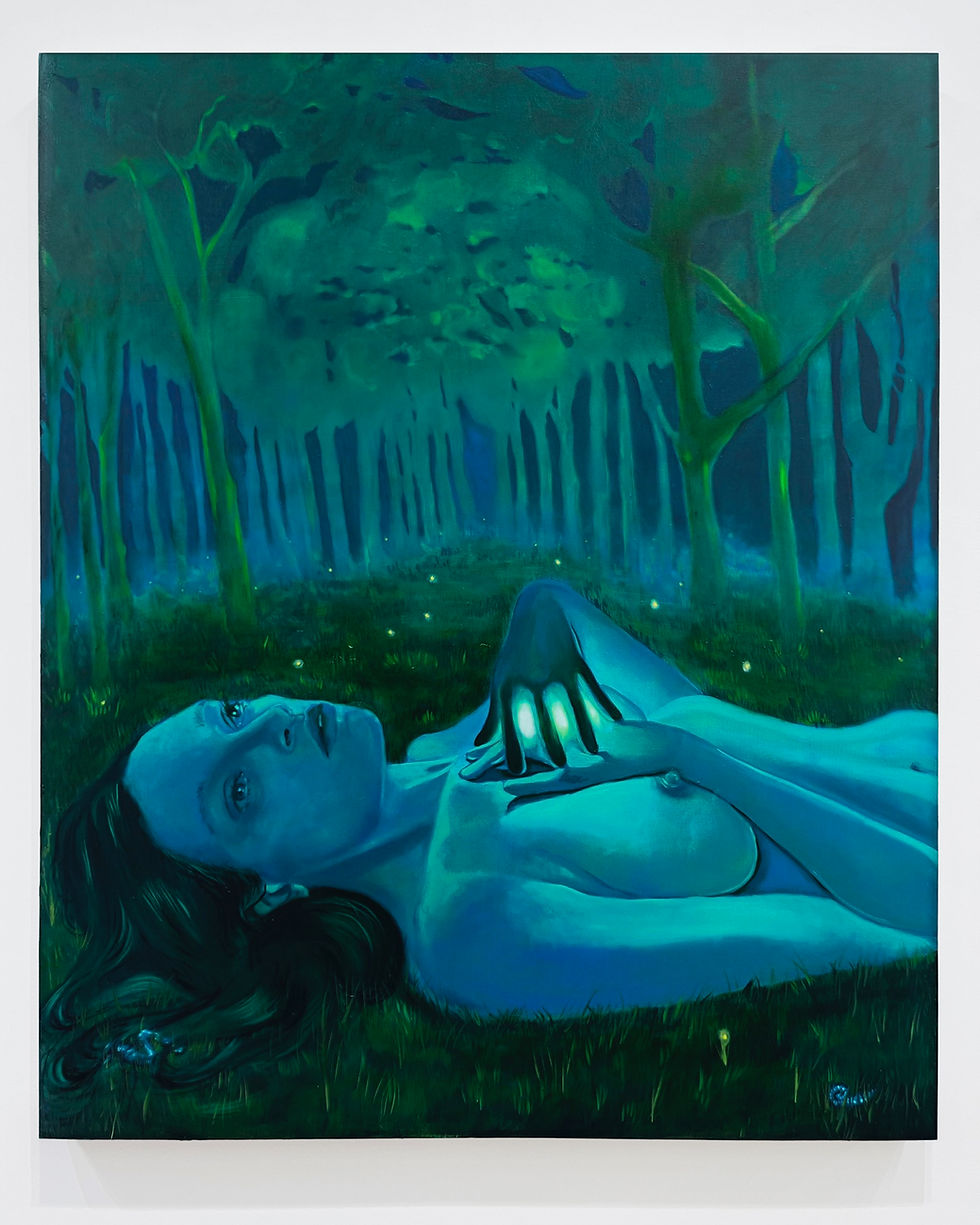

My current paintings explore the tension between being embodied and being absent, the ways the mind protects itself, and the slow process of returning to the present. I like to think of them as returning to the body after a long period of dissociation. I'm interested in the moments where stillness can feel like both safety and paralysis, or where fragmented memory complicates the act of telling a story. The themes I focus on are personal to my experience, but I don’t want them to be limited to me. By working through these states of being visually, I aim to create spaces that allow the viewer to confront the discomfort within them while also finding a sense of recognition, grounding or return.

What are some of the recurring motifs in your work and what do they mean to you?

The figure is often central to my work. I use my own body as a reference, less as self-portraiture and more as a stand-in for the self, any self. My hope is that someone engaging with my paintings can see themselves in the figure, even if it means sitting with something uncomfortable. Sometimes daisy chains will pop up in my paintings. I think of them as almost like a string of memories; something that’s fragile and easily torn. Insects often appear as a motif and even as an extension of the figure. To me, flies represent death. There's something corporeal about the ever-present hum and buzz, like that of lingering trauma in your bones. Worms, burrowing underground, symbolize what is buried or hidden until it resurfaces. Dragonflies, with their long transformation from nymph to adult, embody change and even acceptance. And most significantly, the moth recurs as a glowing form. Moths are drawn to light; they’re searching. In my work, the moth glows itself, pointing inward toward the idea that whatever relief or healing you're searching for is within yourself. These motifs help me build a visual language that conveys trauma, resilience and transformation without always relying on a literal representation that could feel overexposing for me.

Like I mentioned earlier, this series that I’ve been working on is really about a return to the body after a period of dissociation. So I use these motifs as a way to hold onto some of the dreamlike elements of that kind of fugue state while beginning to ground the figure in a more naturalistic world.

What do you hope people feel when they look at your art?

I hope my paintings create a sense of recognition, whether or not the viewer shares my specific experiences is almost irrelevant. Ideally, they spark a sensory response– something within the body that is grounded in a memory or a feeling. For those who have experienced a similar trauma, I hope my work offers relief rather than pain. Showing that you’re not alone in your searching for your body back, in finding grounding and home within yourself again. Broadly, I hope the imagery invites the viewer to reflect on how presence and absence, a flash of a memory, and the feeling of being so far away from yourself can manifest in their own lives. I want the work to open a quiet, intimate relationship between the viewer and the painting, where both vulnerability and resilience are felt. My figures and motifs are personal to me, but they’re also porous; they hold space for others to step into, to feel seen, to be heard, and to remember that even in disconnection, there is a way back home.

What is the most personal piece of art that you’ve ever made, and what’s the story behind it?

I don’t know if it’s necessarily the most personal piece of art that I’ve ever made, since I do make a lot of personal paintings, but it was the piece that kind of cracked all of this open for me, so it’s what is coming to mind. It was in an introductory painting class I took when I decided to go back to college for art. We were asked to create a painting that represented who we were. I painted an abstract female form made of color fields, fragmented and compartmentalized. It was the first time I confronted the divide between my mind and body after being assaulted. Sharing it with the class was one of the first times I talked about it outside of minimal conversations with my family and friends. It was terrifying, but it gave me such a sense of release. It showed me that art could be more than a distraction but a tool to explore, communicate and process what I was carrying. I think that painting marked a turning point in my understanding of art and ultimately led me to what my painting practice is today.

What advice would you offer other artists?

I think experimentation and failure are some of the most important parts of art-making. You often hear the advice to “make a lot of bad art,” and I agree. Through mistakes, you learn what your work wants to be. My advice would be to give yourself permission to create without expectation. For a long time, I didn’t consider myself a “real” artist because my work wasn’t technically perfect or realistic, but I’ve learned that those limitations can open new directions or push you toward a unique or interesting style. Follow the imagery, colors, ideas and materials that call to you, even if you don’t understand why. Eventually, patterns will emerge, and you’ll find meaning in things you didn’t think carried any. If it’s possible, allow for vulnerability in your work. I think raw emotion creates a truth that others can connect with. Even if they don’t always fully understand or relate, there’s a push and pull of knowing and not knowing that is created and makes the work dynamic.

What’s the best compliment someone could give you about your art?

One of the most meaningful compliments I received came from a friend when I was still living in Portland. My best friend and I decided to make a pop-up gallery in our garage. We curated a small show of our and our friends' work. It was the first time I showed work publicly and I was nervous about how it would be perceived. At the time, my paintings were still pretty abstracted figures and I wasn’t yet comfortable framing them directly in relation to my trauma, so my artist statement was pretty vague. This friend walked through the space, looking carefully at each piece, and when he spoke to me afterward, he told me that my paintings had made him cry. I hadn’t set out to make the work painful, but I was deeply moved that he could feel how emotional and vulnerable they were for me to make. It was the first time I felt like I had honestly communicated something beyond words, that the imagery itself somehow carried the weight of what I had been carrying.