Patchwork Collecting: BIPOC, Outsider, and Vintage Art for Real Homes

- 18 minutes ago

- 6 min read

By Charlie Li, founder of Curio Atelier

There is a kind of art collection that rarely appears in glossy interiors or market reports.

It grows slowly in rental apartments and walk-up condos, in shared houses, basement suites, and small city kitchens. It is built from saved screenshots, late-night messages with artists, thrift-store discoveries, trades, one or two splurges, and pieces carried from one move to the next. From outside, it might not even be recognized as a collection. Inside the life attached to it, it functions exactly like one.

This is the kind of collecting that sits at the heart of Curio Atelier.

It can be thought of as patchwork collecting: a way of building a home with BIPOC and self-taught or outsider voices, emerging artists, and vintage works whose makers may be unknown but whose presence is undeniable. The goal is not a perfectly coherent, capital-C Collection. The goal is something honest, layered, and alive enough to belong in a real, lived-in space.

Who Counts As a Collector

The idea of a collector still carries weight. It often implies a particular income bracket, a certain kind of education, familiarity with gallery language, and an ease in spaces that can be intimidating. Without those signals, many people assume they are simply decorating, not collecting.

At the same time, there has always been another reality. People acquire drawings from friends and neighbours, paintings from community shows, a landscape from a trip, an odd portrait that no one else in the family wanted. These objects do not announce themselves as a collection. Yet together they arrange memory, identity, and value on the walls.

Curio Atelier emerged from the sense that there is an entire ecosystem of artists—especially BIPOC, self-taught, outsider, or otherwise non-institutional—whose work is compelling and deeply collectible but not always positioned as such. Alongside them are vintage works that have already passed through other homes and hands: unsigned watercolours, mid-century drawings, small devotional works, portraits of unknown sitters. Rather than dividing them into hierarchies, patchwork collecting places them in dialogue.

In this model, collecting is not reserved for a narrow group. A collector is simply someone who chooses to live with art, over time, with intention.

Artists in the Patchwork

The artists who end up in these patchwork constellations rarely share a single visual style. They are linked more by stakes than by surface.

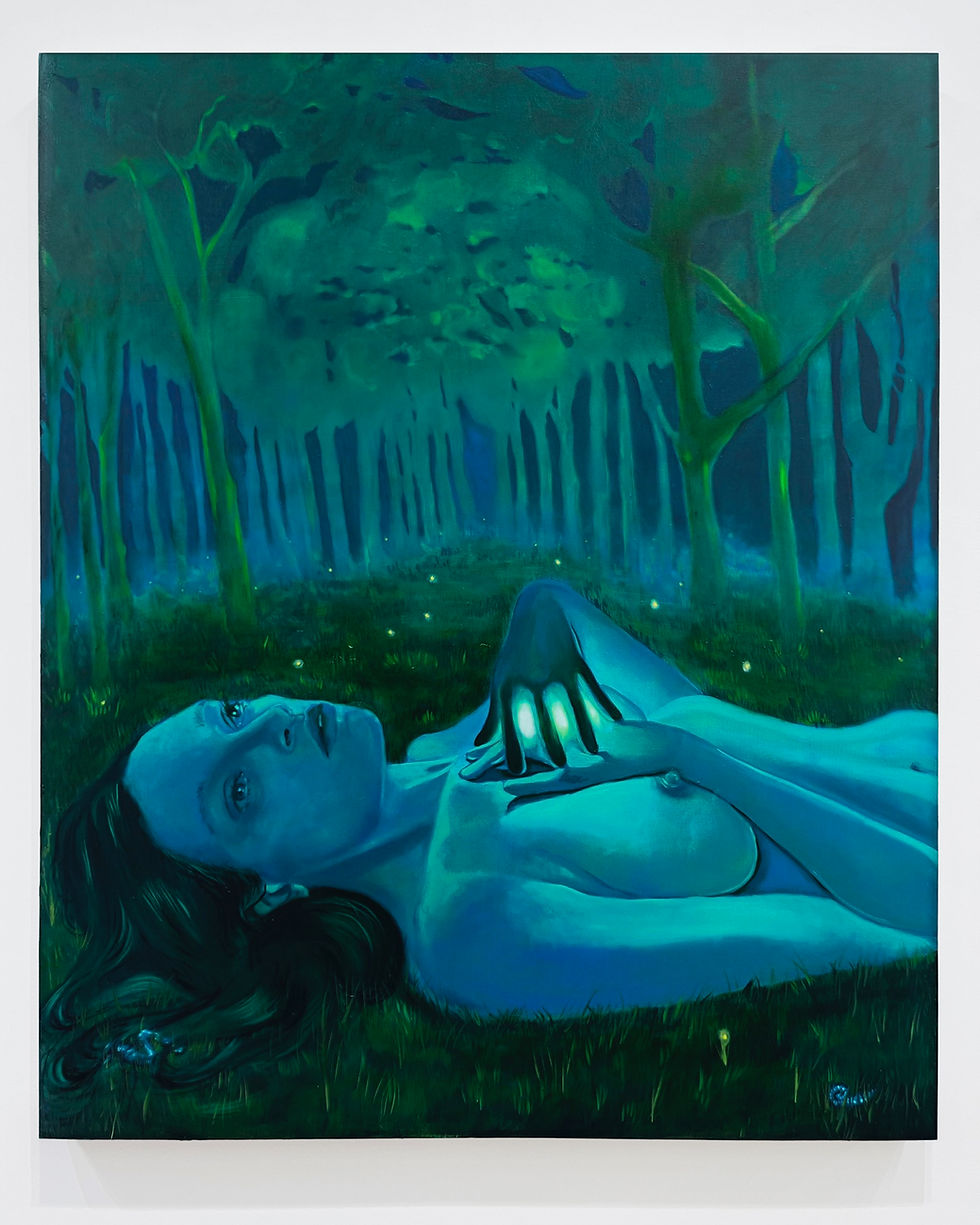

Some are self-taught folk or outsider artists who work through disability, illness, or neurodivergence, and use painting as a stabilizing force in their daily lives. Others are Indigenous artists rebuilding visual language after generational rupture, folding ancestral stories into a contemporary graphic vocabulary. There are portrait painters whose figures are full-bodied, imperfect, and emotionally complex, holding soft forms of resistance inside their gaze and posture. There are narrative painters whose surreal worlds grow out of fairy tales, research, and personal history, where animals, women, and landscapes share the same psychological weight.

Certain artists are labelled “outsider” because their route to art does not run through institutions: no formal schooling, limited access to networks, geographic distance, economic constraint. Others have degrees and exhibitions but find their work held at the margins for reasons of race, class, gender, or simply because it does not fit neatly into a trend.

What unites them is sincerity. The work carries real stakes: it is a site of thinking, coping, remembering, and imagining, rather than a purely strategic object.

Placed beside vintage pieces, these works often feel unexpectedly connected. An anonymous harbour scene from the 1940s and a contemporary painting by a living artist can both read as attempts to register a life and a time. In a patchwork collection, those attempts share the wall.

Vintage As a Bridge

Vintage art can occupy an uncomfortable middle ground. At one end are high-value historical works with heavily documented provenance; at the other, anonymous prints and paintings treated mainly as decor. Between those poles lies a wide field of original work with modest price points and quiet histories.

Within patchwork collecting, vintage functions less as a bargain category and more as a bridge. It links past and present and creates an entry point for people who did not grow up around art or in rooms where collecting was openly discussed. A small oil painting of a landscape, a student work from the mid-twentieth century, or a delicate drawing with a half-legible signature can anchor a corner as effectively as any contemporary piece. These objects arrive already seasoned by time, with surfaces that hold light differently and carry subtle evidence of earlier lives.

For many new collectors, a vintage work becomes the first step into living with original art. It is often more financially accessible and less intimidating than commissioning or buying directly from a contemporary artist. Once someone has experienced what it means to share daily space with a single, real artwork—the way it registers different weather, the way it accompanies mood shifts—it becomes easier to consider bringing in work by living artists whose voices feel urgent and present.

The value of these older pieces, then, is not simply financial. They help soften the distance between art over there and art at home.

Outsider, Insider, and the Decision to Say Yes

Labels such as BIPOC, outsider, or self-taught can illuminate structures of exclusion, but they can also flatten experience. At Curio Atelier, the emphasis lies less on classification and more on orientation: whose stories and images have historically been sidelined, and what it might mean to recentre them on domestic walls.

In practice, patchwork collecting is built through a series of modest decisions over time. Someone chooses a drawing by a local painter instead of another mass-produced print. Someone decides that a self-taught artist working in a small town deserves the same seriousness taken for granted in more established settings. Someone brings home a painting by an artist of colour whose figures counter centuries of narrow representation.

These choices happen quietly—in emails, studio visits, art fairs, and online exchanges—but they move resources and attention in real ways. Over years, they coalesce into a collection that reflects a different set of values than those that dominate auction catalogues or institutional narratives.

The intention is not to save anyone. It is to recognize that a collection can be a small redistribution of attention, care, and money toward artists whose work might otherwise remain peripheral.

Real Homes

Patchwork collections tend to live in spaces where life is thick. These are homes with books stacked on bedside tables, plants leaning toward the one good window, laptops open on dining tables, and jackets draped over the backs of chairs. They might be shared apartments, small family homes, or studio-living room hybrids where work and rest are never fully separate.

Art in these spaces cannot rely solely on aesthetic harmony. It has to do practical emotional work. A single portrait above a desk may become a kind of witness during late nights. A surreal landscape in a hallway can turn a daily route between rooms into a momentary imaginative detour. A folk painting in a child’s room can quietly inform that child’s sense of colour, body, and narrative long before any formal language for art is learned.

None of these roles is dramatic, but they are significant. Over time, the accumulation of such pieces shapes how a household understands itself and the world around it.

Curio in Context

Within the broader art ecosystem, Curio Atelier occupies an in-between position. It is neither a blue-chip gallery nor a purely commercial decor shop. It is a small, evolving space that works closely with a specific group of artists and with collectors who are often building their first or second serious pieces.

The work we bring in reflects a few consistent commitments: a focus on emerging and often underrepresented artists; a respect for vintage works as active participants rather than mere backdrop; and a belief that collecting can unfold slowly and thoughtfully, at scales that match ordinary lives.

Patchwork collecting does not require perfection. It begins with a single decision to live with one painting, drawing, or print that feels honest. Over time, more decisions follow. Walls change. Rooms start to hold different energies. The visual canon inside a home expands to include artists and histories that were once distant.

While large-scale art structures continue with their fairs, lists, and cycles of attention, small collections keep forming quietly in everyday spaces. These patchworks—BIPOC, outsider, vintage, emerging, stitched together over years—carry a different story about who art is for and how it can live with people.

That is the story Curio Atelier is trying to participate in: a story of real homes, real artists, and collections that do not need to be perfect to matter.